Category Archives: Italy

What a baker from ancient Pompeii can teach us about happiness

Art Media/Print Collector via Getty Images

Nadejda Williams, University of West GeorgiaIn a testament to its resiliency, happiness, according to this year’s World Happiness Report, remained remarkably stable around the world, despite a pandemic that upended the lives of billions of people.

As a classicist, I find such discussions of happiness in the midst of personal or societal crisis to be nothing new.

“Hic habitat felicitas” – “Here dwells happiness” – confidently proclaims an inscription found in a Pompeiian bakery nearly 2,000 years after its owner lived and possibly died in the eruption of Vesuvius that destroyed the city in A.D. 79.

What did happiness mean to this Pompeiian baker? And how does considering the Roman view of felicitas help our search for happiness today?

Happiness for me but not for thee

The Romans saw both Felicitas and Fortuna – a related word that means “luck” – as goddesses. Each had temples in Rome, where those seeking the divinities’ favor could place offerings and make vows. Felicitas was also portrayed on Roman coins from the first century B.C. to the fourth century, suggesting its connection to financial prosperity of the state. Coins minted by emperors, furthermore, connect her to themselves. “Felicitas Augusti,” for example, was seen on the golden coin of the emperor Valerian, iconography that suggested he was the happiest man in the empire, favored by the gods.

By claiming felicitas for his own abode and business, therefore, the Pompeiian baker could have been exercising a name-it-claim-it philosophy, hoping for such blessings of happiness for his business and life.

NumisAntica, CC BY-SA

But just beyond this view of money and power as a source of happiness, there was a cruel irony.

Felicitas and Felix were commonly used names for female and male enslaved persons. For instance, Antonius Felix, the governor of Judaea in the first century, was an ex-slave – clearly, his luck turned around – while Felicitas was the name of the enslaved woman famously martyred with Perpetua in A.D. 203.

Romans perceived enslaved people to be proof of their masters’ higher status and the embodiment of their happiness. Viewed in this light, happiness appears as a zero-sum game, intertwined with power, prosperity and domination. Felicitas in the Roman world had a price, and enslaved people paid it to confer happiness on their owners.

Suffice it to say that for the enslaved, wherever happiness dwelled, it was not in the Roman Empire.

Where does happiness really dwell?

In today’s society, can happiness exist only at the expense of someone else? Where does happiness dwell, as rates of depression and other mental illness soar, and work days get longer?

Over the past two decades, American workers have been working more and more hours. A 2020 Gallup poll found that 44% of full-time employees were working over 45 hours a week, while 17% of people were working 60 or more hours weekly.

The result of this overworked culture is that happiness and success really do seem to be a zero-sum equation. There is a cost, often a human one, with work and family playing tug-of-war for time and attention, and with personal happiness the victim either way. This was true long before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studies of happiness seem to become more popular during periods of high societal stress. It is perhaps no coincidence that the longest-running study of happiness, administered by Harvard University, originated during the Great Depression. In 1938, researchers measured physical and mental health of 268 then-sophomores and, for 80 years, tracked these men and some of their descendants.

Their main finding? “Close relationships, more than money or fame … keep people happy throughout their lives.” This includes both a happy marriage and family, and a close community of supportive friends. Importantly, the relationships highlighted in the study are those based on love, care and equality, rather than abuse and exploitation.

Just as the Great Depression motivated Harvard’s study, the current pandemic inspired social scientist Arthur Brooks to launch, in April 2020, a weekly column on happiness titled “How to Build a Life.” In his first article for the series, Brooks loops in research showing faith and meaningful work – in addition to close relationships – can enhance happiness.

Finding happiness in chaos and disorder

Brooks’ advice correlates with those findings in the World 2021 Happiness Report, which noted “a roughly 10% increase in the number of people who said they were worried or sad the previous day.”

Faith, relationships and meaningful work all contribute to feelings of safety and stability. All of them were victims of the pandemic. The Pompeiian baker, who chose to place his plaque in his place of business, likely would have agreed about the significant connection among happiness, work and faith. And while he was not, as far as historians can tell, living through a pandemic, he was no stranger to societal stress.

It’s possible his choice of décor reflected an undercurrent of anxiety – understandable, given some of the political turmoil in Pompeii and in the empire at large in the last 20 years of the city’s existence. At the time of the final volcanic eruption of A.D. 79, we know that some Pompeiians were still rebuilding and restoring from the earthquake of A.D. 62. The baker’s life must have been filled with reminders of instability and looming disaster. Perhaps the plaque was an attempt to combat these fears.

After all, would truly happy people feel the need to place a sign proclaiming the presence of happiness in their home?

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Or maybe I’m overanalyzing this object, and it was simply a mass-made trinket – a first century version of a “Home Sweet Home” or “Live, Laugh, Love” placard – that the baker or his wife picked up on a whim.

And yet the plaque reminds of an important truth: people in antiquity had dreams of and aspirations for happiness, much like people do today. Vesuvius may have put an end to our baker’s dreams, but the pandemic need not have such a permanent impact on ours. And while the stress of the past year-and-a-half feels may feel overwhelming, there has been no better time to re-evaluate priorities, and remember to put people and relationships first.![]()

Nadejda Williams, Professor of Ancient History, University of West Georgia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Unearthing Falerii Novi’s secrets in the hot Italian summer: an archaeologist reports from the dig

Emlyn Dodd, Macquarie UniversityLocated about 50 kilometres north of Rome, the ancient city of Falerii Novi lies buried beneath agricultural fields and olive groves. City walls still stand in an almost complete circuit and visitors pass through the monumental western gate to enter the site.

The findings from detailed ground-penetrating radar mapping were published a year ago. Now the real business of digging has begun.

At the ancient site, our teams have already discovered remnants of daily life from more than 2,000 years ago. We hope excavation will yield rare insight into antiquity with its preserved urban layout, just like at the buried city of Pompeii.

A ‘new’ city

Ancient authors Polybius and Livy tell us the city was founded by Rome in 241 BCE, following the defeat of a revolt led by the inhabitants of nearby Falerii Veteres (now Civita Castellana). According to one source, 12th-century chronicler Zonaras, Rome forcibly resettled the defeated Faliscans to a less defensible location — Falerii Novi or “new Falerii”. Its construction, intimately associated with the Roman road Via Amerina, is a rare example of preserved Roman Republican urban planning.

Shutterstock

The city was occupied through Roman antiquity and to the early medieval period (6th and 7th centuries CE). It was on a key strategic trading route leading north from Rome, perhaps from Ponte Milvio, through central Italy.

We know little of its later history, except that the still-standing church of Santa Maria di Falleri was founded by Benedictines in 1036, disbanded in 1392 and the building was in ruins by 1571. It is now largely restored with excavated Roman roads visible beneath the floor.

When and how Falerii Novi became buried remains a mystery. How did such a large walled city become covered in so much soil? And what happened in late antiquity to cause its abandonment? The current dig may answer those questions too.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more:

Cave of Horror: fresh fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls echo dramatic human stories

Old digs, new tricks

Three scattered attempts at excavation have been made previously. From 1821–30 a Polish team explored around the theatre area and in a (now lost) residential and commercial street-side strip. Towards the end of the 19th century work was attempted at a number of locations near city gates. And local Soprintendenza archaeologists looked at an area on the western flank of the suspected forum from 1969-75.

The site’s historical importance and immense potential, alongside developing technology, led to renewed archaeological attempts.

From 1997–8, topographic survey and surface collection were combined with magnetometry to get a broader sense of the city’s urban layout, chronology and neighbourhoods. This revealed structures including theatres, bathhouses, villas, temples and a forum a few feet under the ground.

Later, this was extended outside the city walls, revealing tombs, buildings and roads leading towards an amphitheatre.

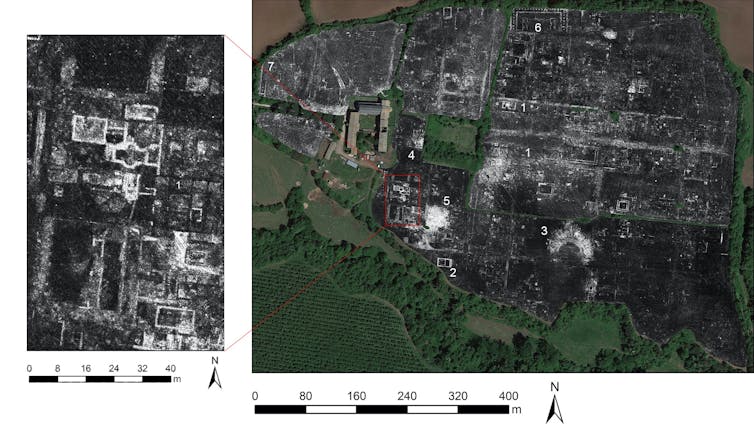

L. Verdonck, Google Earth, Antiquity Journal

Recently a survey of the entire city using cutting-edge ground-penetrating radar produced sharper images and created a three-dimensional rendering of sub-surface features. Completely new structures were revealed, including a colossal structure, over 100 metres long, thought to be a colonnaded temple against the north city wall.

The detailed map produced by these efforts is now being used to pin-point excavation areas.

Read more:

Six reasons to save archaeology from funding cuts

Breaking new ground

I’m one of the people working on the first season of systematic excavation (started in June) by a collaborative team from the Universities of Harvard and Toronto, the British School at Rome and under the concession of the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per la Provincia di Viterbo e l’Etruria Meridionale.

We have opened a series of over 120 small test pits across the site. These will provide an initial understanding of various neighbourhoods — domestic, productive, religious, civic — along with chronological and spatial densities of habitation and material.

We start digging at 8am, stopping for breaks through the heat of the day, and finishing around 4pm. The work is sweaty and dirty in the hot Italian summer, but the promise of this site excites and energises everyone.

B. Fochetti, Author provided

Work so far has revealed clues to the early occupancy of the site soon after founding in 241 BCE. What archaeologists call “black gloss ware” — a typical type of Roman Republican pottery — has been pulled out of test pits. Small pieces of Roman glass, metal slag and other ceramics are also present. Pieces of shimmering, iridescent green-glazed medieval pottery were also found, highlighting continued, post-Roman occupancy.

Next, larger-scale trenches will be opened at areas of interest. Perhaps around domestic structures and insulae (groups of buildings). Revealing the macellum marketplace, might tell us what was bought and sold, what commercial structures looked like and who was engaged in these activities. A taberna (typically a one-room shop) on the edge of the central forum may tell us about the goods and services on offer.

Read more:

A batshit experiment: bones cooked in bat poo lift the lid on how archaeological sites are formed

Testing the soil

A team from Ghent University is following up previous work on site with Cambridge University. This year they are taking core samples (called augering) up to 5 metres below the current ground level. This gives archaeologists a snapshot of the site across time: human impacts on the landscape, environmental data, habitation and material changes.

A. Hoffelinck

Early results are starting to show the very real and profound effect of Roman settlement in the area. Pottery from cores also indicates occupancy over a long time, perhaps even earlier than told to us by Polybius and Livy.

Work will continue in 2022 when the first large trenches are opened and a new view of life at Roman Falerii Novi is illuminated.

Emlyn Dodd, Assistant Director of Archaeology, British School at Rome; Honorary Postdoctoral Fellow, Macquarie University; Research Affiliate, Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.