Lydia Edwards, Edith Cowan University

Masks have emerged as unlikely fashion heroes as the COVID-19 pandemic has developed. Every conceivable colour and pattern seems to have become available, from facehuggers to Darth Vader to bejewelled bridal numbers.

Many show how brevity and style can combine to protect the wearer, offsetting the fear the sight of a respiratory or surgical mask usually inspires.

Some, like those produced by not-for-profit enterprises including the Social Studio and Second Stitch, use on-trend fabrics and benefit both the wearer and the makers. Meanwhile, an Israeli jeweller has designed a white gold, diamond-encrusted mask worth US$1.5 million (A$2.1 million).

Yet, masks remain fundamentally unnerving. Mostly intended to either protect or disguise, they are designed to cover all or part of the face. In societies where emotions are read through both eyes and mouth, they can be disorienting.

In many places around the globe, masks have played an important role in conveying style, spirituality and culture for thousands of years. They have been a part of western fashion for centuries. Here are some of the highlights (and lowlights) of masks as fashion items.

Read more:

How should I clean my cloth mask?

Silenced by the vizard

“And make our faces vizards to our hearts/Disguising what they are”

– Macbeth

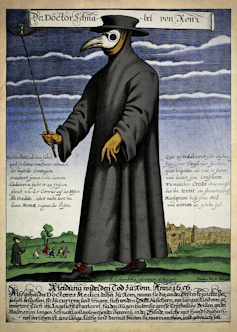

One of the most bizarre accessories in 16th-century fashion was the vizard, an oval-shaped mask made from black velvet worn by women to protect their skin whilst travelling.

Wikimedia

In an age where unblemished skin was a sign of gentility, European women took pains to avoid sunburn or significant sun tan. Two holes were cut for the eyes, sometimes fitted with glass, and an indentation was created to accommodate the nose. Disturbingly, they did not always have an opening for the mouth.

To hold the mask in place, wearers gripped a bead or button between their teeth, prohibiting speech. To the contemporary feminist, the mask raises associations with the scold’s bridle: a method of torture and public humiliation for gossiping women and suspected witches.

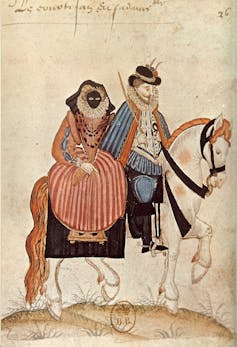

During the following century, masks continued to be fashionable although the guise of protection gave way to mystique and desire. The small “domino” mask – seen in a 17th century Netherlands example below and still worn by superheroes from Batman to Harley Quinn – covered the eyes and tip of the nose. It was usually made from a strip of black fabric. For warmer months, a lighter veiling could be substituted.

Rijksmuseum

Read more:

Beware of where you buy your face mask: it may be tainted with modern day slavery

Masquerade and desire

Venice has long been associated with masks, thanks to its history of carnival and masquerade. Their theatrical nature might lead to an assumption masks were always worn to deceive or seduce. Travellers expecting a masked amoral free-for-all in the early 18th century were surprised at how “innocent” the accessory really was in everyday life.

When worn at a masquerade, masks encouraged “safe” contact between the sexes – bringing them close enough to mingle but maintaining the social distance between strangers that etiquette required. In this scenario, masks also encouraged a kind of egalitarianism by allowing people of disparate social classes to mix – a freedom never allowed in normal social gatherings.

The gnaga mask, with its cat shape, allowed men to dress as women and skirt Venetian homosexuality laws. Venetian prostitutes were at various times prohibited from wearing or required to wear masks in public, yet married women were required to wear masks to the theatre, fostering an association between masks and sex.

Unsplash/Llanydd Lloyd, CC BY

Conversely, the infamous Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, published annually between 1757 and 1795, provided a catalogue of prostitutes to hire in London. One entry from 1779 described a woman who …

by her own confession has been a votary to pleasure these thirty years, she wears a substantial mask upon her face, and is rather short.

John Cleland’s controversial 1748 book Memoirs of Fanny Hill describes Louisa, a prostitute, being made “violent love to” by a “gentlemen in a handsome domino” as soon as her own mask was removed.

Charming possibilities

“A mask tells us more than a face”, wrote Oscar Wilde in his 1891 dialogue Intentions, yet by the 19th century the mask as fashion accessory was démodé. Masks were generally only mentioned in newspapers and fashion magazines when referring to fancy dress and masked balls, which still took place in the homes of the wealthy.

“Society is a masked ball”, wrote one American columnist in 1861 mirroring Wilde’s famous quote, “where everyone hides his real character, and reveals it by hiding”.

Although masks were no longer recommended for maintaining a pale complexion, women’s faces were still covered by veiling in certain situations: including, for the first time, weddings. Ironically, one Australian fashion column in 1897 decried the fashion, stating:

Veils are largely responsible for poor complexions … This fine lace mask – for it is nothing else – hinders the circulation … but does far more injury by keeping the face heated.

As if this were not enough, veils blew dust from the street into “open pores” and retained dirt, redistributing it onto the skin every time it was worn.

Shutterstock

Veiling still had some fans, who touted its health and beauty benefits, and connotations of intrigue and excitement. “It suggests such charming possibilities beneath it”, a columnist in The Australasian wrote in 1897.

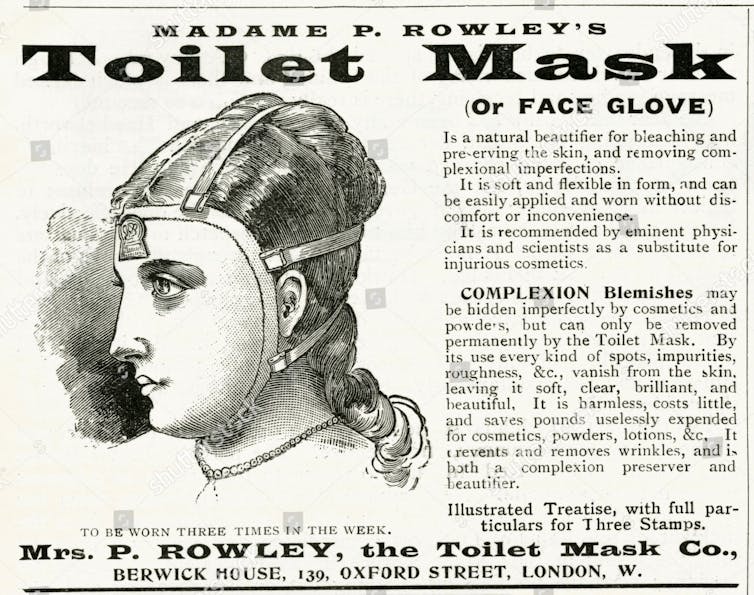

Fashionable or not, some masks were still worn behind closed doors. Enter the most bizarre masked accessory since the vizard: the toilet mask or “face glove”.

Devised by a Madame Rowley in the 1870s-80s, the rubberised full-face covering was advertised as an:

aid to complexion beauty … treated with some medicated preparation … the effects of the mask when worn at night two or three times in the week are described as marvellous.

Advertisements for these precursors to today’s sheet mask beauty treatments contained testimonials from women who claimed to be cured of freckles and wrinkles.

Veils and visors

The advent of the automobile in the early 20th century brought a whole new fashion range into the public arena. Motorists needed protection from weather, dust and fumes, so accessories had to be practical. For women, protection took the fashionable form of coats and face coverings.

Veils and hoods were wrapped around stylish large hats of the day, and fastened under the chin so that the entire face was safely covered.

Advertisements in the early 1920s describe a “complete face mask” for drivers – ostensibly men as the accessory “buttoned to the cap and [is] equipped with an adjustable eye shield against glaring headlights”.

A design for women in 1907 was described as a “window hood”, which completely engulfed the hat beneath and closed with a drawstring around the neck. It had a gauze “window” for the eyes and another smaller opening at the mouth.

By the swinging 1960s, the cultural and sartorial landscape couldn’t have been more different – and yet, masks made an unlikely appearance in “space age” fashion championed by designers such as André Courrèges and Pierre Cardin. Metallic mini dresses and one-piece suits were topped with “space helmets” that left an opening for the entire face or eyes.

More commonly adopted were plastic visors worn separately or as part of a hat, sometimes covering forehead to chin and taking on the appearance of a welders’ shield – or indeed, the face shields worn by health workers today.

Sunglasses, a kind of mask in their own right, were taken to the extreme by Courrèges with his infamous solid white shades with only a slit for light. Life described this as a “built-in squint” in 1965 – a design that “dangerously narrows the field of vision”.

Read more:

The fashionable history of social distancing

What goes around …

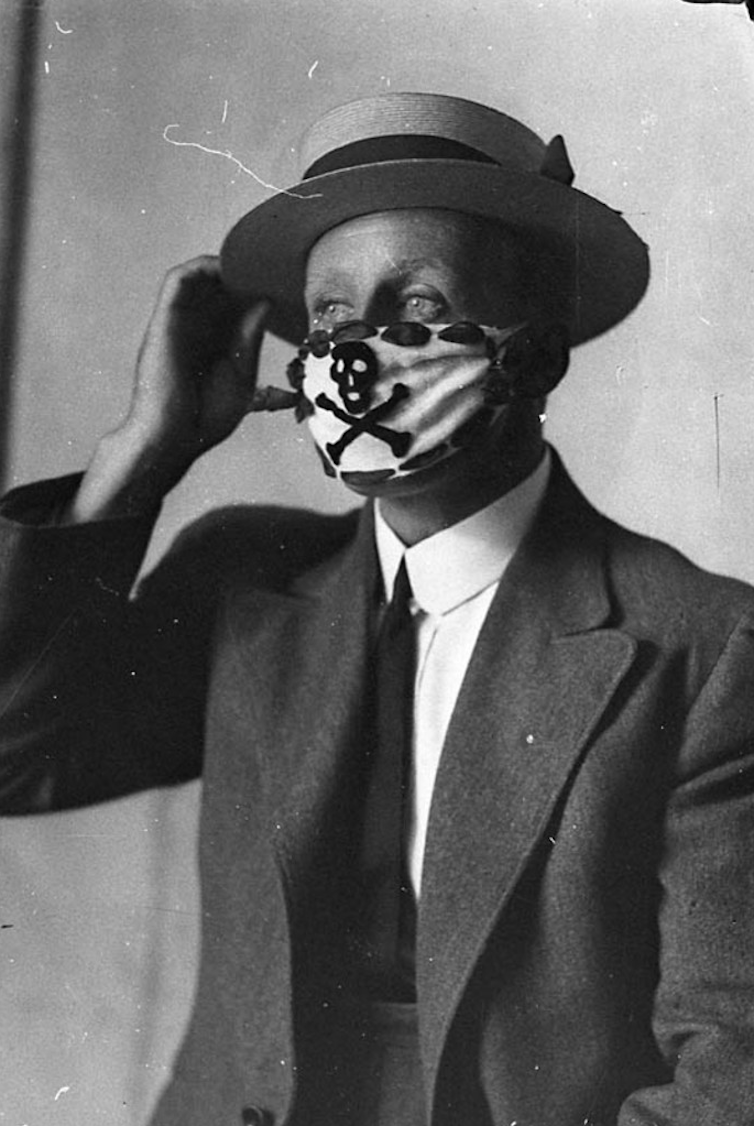

Discussions during the 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic around whether masks would be a fad, how long they would be required, and how to create your own at home, seem eerily prescient now.

This darkly comic mask from 1918 demonstrates the same wish for ingenuity and levity that exists today:

State Library of NSW/Flickr

Lebanese fashion designer Eric Ritter has sported a similarly macabre aesthetic. He was already thinking and writing about masks on Instagram in January before coronavirus spread around the world …

On growing up without a mask

On being forced to wear a mask

On ecstatically removing a mask

On picking a mask back up

ericmathieuritter/Instagram

In Australia, entertainer Todd McKenney has launched an online marketplace for costume designers to make and sell one-of-a-kind masks directly to the public.

Face masks don’t have to be created by artists, designers or couture fashion houses to make them appealing. But a look through our fashion history shows that ingenuity and humanity have long influenced our face wear – whether for the purposes of allure, space travel or pandemic protection.![]()

Lydia Edwards, Fashion historian, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.