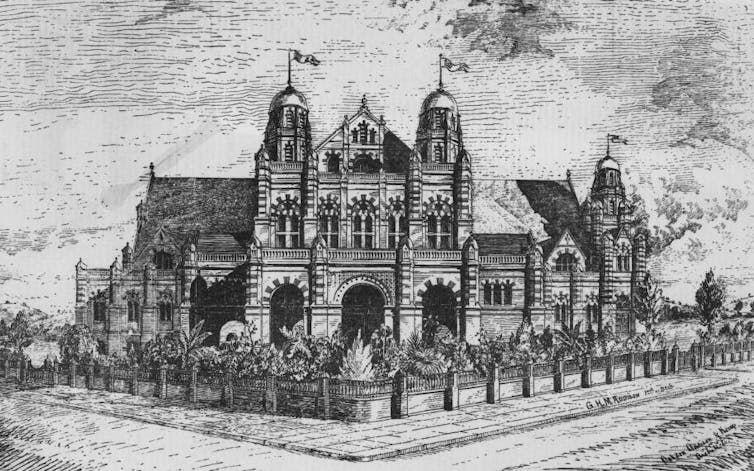

Queensland State Library

Emma Christopher, UNSWThere are moves afoot to scrub colonial businessman Benjamin Boyd’s name from the map. The owners of historic Boydtown on the NSW south coast are planning to change its name, while Ben Boyd National Park may also be renamed. Residents in North Sydney will take part in a survey to rename Ben Boyd Road, too.

The reason: Boyd’s links to “blackbirding” in the 19th century.

Blackbirding was a term given to the trade of kidnapping or tricking Pacific Islanders on board ships so they could be carried away to work in Australia.

Boyd instigated this practice in the late 1840s, bringing the first group of Pacific Islanders to work on land in the Australian colonies. Although his scheme ultimately failed, other labour traders would deliver approximately 62,000 islanders to Queensland and NSW between the 1860s and 1900s.

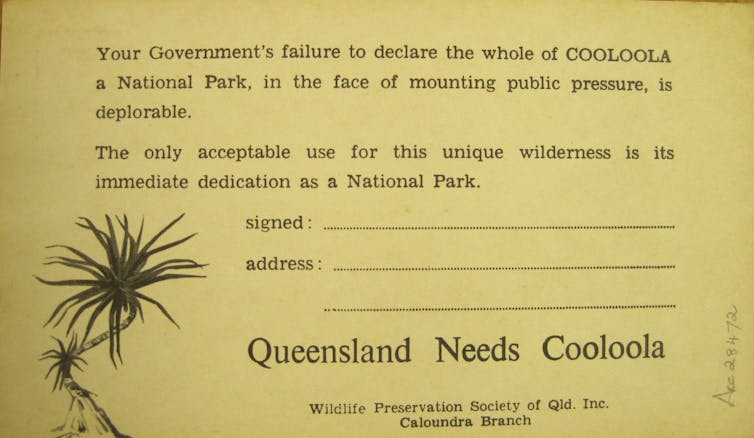

The moves to rename the NSW sites are largely due to Australian South Sea Islanders’ struggles for recognition of what their ancestors endured. They often prefer the term slavery to indentured labour and demand full acknowledgement of what happened.

One way this might be achieved is by tracing Pacific Islander blackbirding back to its roots and placing it within the global context of slavery.

This history — painful and provocative as it might be — offers a way to bridge the divisions between those who are proud of Australia’s sugar pioneers and Australian South Sea Islanders who are still dealing with the losses from this ugly past.

Read more:

Monumental errors: how Australia can fix its racist colonial statues

Boyd’s history with slavery

To take this broader perspective, we need to reexamine Boyd’s early life. Boyd was the son of a wealthy London slave trader, Edward Boyd, whose business shipped several thousand enslaved people to sugar plantations in the Caribbean and fought against the abolition of the slave trade in 1807.

This matters. Benjamin Boyd claimed to be a self-made man, but his education, home life, connections and worldview were fostered by his father’s profession and the wealth it had created.

State Library of New South Wales

As Marion Diamond wrote in her 1988 biography of Boyd, he had grown up in Britain with an African servant named Dick. As a child aboard one of Edward Boyd’s slave ships, Dick had become too sick to make a profit at market. Instead of being thrown overboard as “refuse”, as was usual, Dick was taken to Britain to be a servant.

Benjamin’s preconceived ideas of “Black” labour and his own place in the world were based on these early experiences of being served tea by Dick.

Read more:

Think slavery in Australia was all in the past? Think again

He was hardly alone among blackbirders in having such a background. It would be extraordinary if he had been.

The reason the importation of Pacific labourers took off in the 1860s, following Boyd’s earlier example, was the fledgling Australian sugar industry.

Sugar had profoundly changed the Americas by this time, creating unparalleled wealth for Britain, France, the Netherlands and other colonisers. It also played a central role in industrialisation.

Sugar’s voracious labour demands — and massive profit margins — accounted for a vast percentage of the 12 million or so African captives delivered for sale in the Americas.

Sugar and slavery created many of Britain’s richest men. And when slavery was abolished in much of the British empire in 1833-34, sugar planters gained by far the biggest compensation payouts for the loss of their human property.

State Library of New South Wales

Australian-Caribbean connections

It is no wonder many of Australia’s sugar pioneers and blackbirders had family backgrounds, fortunes and/or experiences from the slave-sugar complex of the Caribbean (as well as Mauritius in the Indian Ocean). I have so far found more than 200 such people who came to Australia to start again.

Among them was Louis Hope, celebrated as Queensland’s sugar pioneer, who came from a West Indies slave trading and owning family. Ormiston House, Hope’s former home, contains a fawning plaque to him, which mentions neither his pioneering use of South Sea Islander workers, nor his family’s past connections to slavery.

John Ewen Davidson, the “doyen” of the Mackay sugar industry, was also from one of the wealthiest slave-owning dynasties in the West Indies going back four generations.

Read more:

Was there slavery in Australia? Yes. It shouldn’t even be up for debate

Caribbean planters and their children did not only bring money to Australia, but also ideas of how sugar could best be grown. They were experts in what labourers should look like: dark-skinned, cheap and easy to control by restricting options for escape.

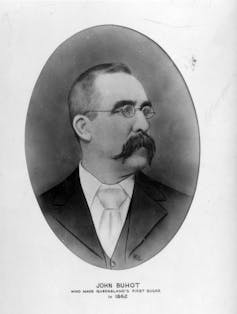

They sought managers from the West Indies to run their plantations, such as John Buhot of the Barbados, for whom there is a plaque in Brisbane’s Botanic Gardens. Buhot’s parents were minor slave owners and he had trained there as a sugar boiler and manager.

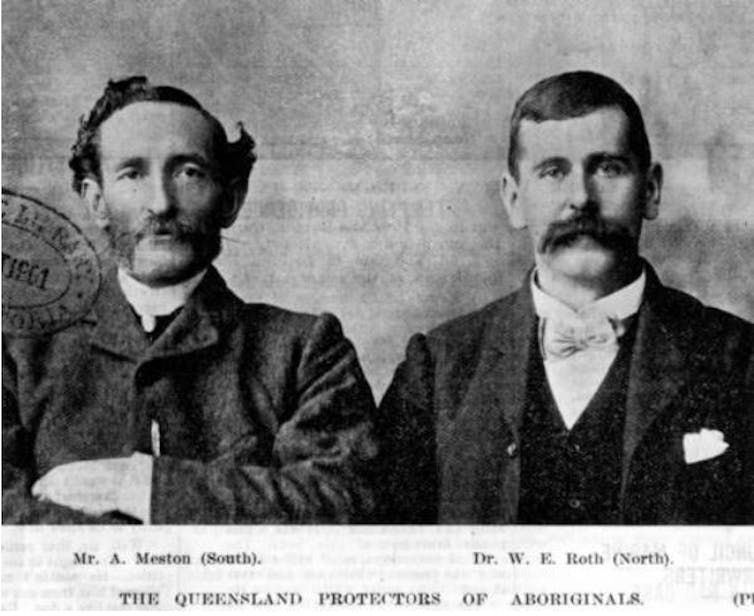

Queensland State Archives

Other managers were recruited from the US, Cuba and Brazil, where slavery was either just ending or not yet abolished.

In other words, the men who had experience managing enslaved African people in the Americas were sought to oversee Pacific Islanders, despite them being not legally enslaved in Australia. It was thought to be expedient.

The naming of Australian places

These connections to the Atlantic slavery trade dot Australia. The central NSW coastal suburb of Tascott, for instance, is named for Thomas Alison Scott, who had previously worked at his uncle’s slave-trading company and then as a manager at his father’s plantation in Antigua.

State Library of Queensland

When Scott arrived in Australia, he appropriated the sugar-growing successes of a black Antiguan slave as his own.

For others, the use of Caribbean names for Australian locations was both commemorative and hopeful of the wealth they hoped to reproduce. The Brown brothers, whose mother was from the West Indies, settled on the Fraser Coast and named their sugar plantation Antigua. This name remains in use today.

Far more notable were the Longs, who had been among the wealthiest and most influential slaveholders in Jamaica since 1655. They also relocated to Queensland in the 19th century and named their plantation north of Mackay for Cuba’s capital, Habana.

Connections to the Caribbean were celebrated in this way even after Britain became fervently anti-slavery.

If Pacific labour is seen not as an Australian peculiarity but instead as part of the global slave trade, it becomes far easier to grasp the scope of the grief and disadvantage that Australian South Sea Islanders are still dealing with.

As Pacific Islanders have been demanding for some time, we need to examine and confront this history before we can move forward.![]()

Emma Christopher, Scientia Fellow, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.